surreal exhibits - sublime architecture

While in St Petersburg on a first time visit to this part of south west Florida, we had the opportunity to visit the Dali Museum. Now, I’ve seen quite a bit of Mr Dali’s work at various museums around the world over the years, but this venue houses what is probably the most comprehensive collection of his work. I particularity liked the painting of his other half Gala, which at a distance, morphs into a portrait of President Abraham Lincoln!

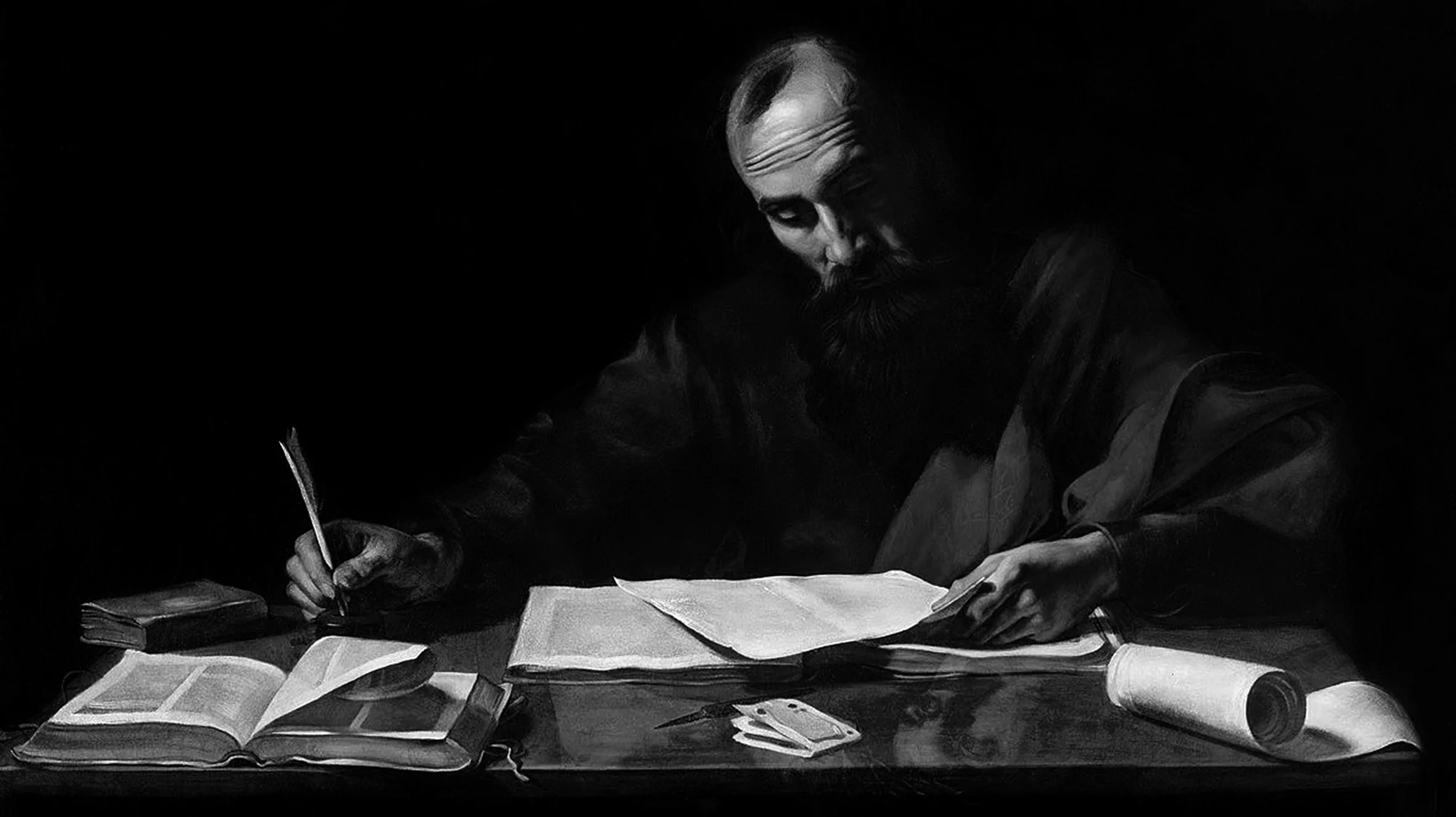

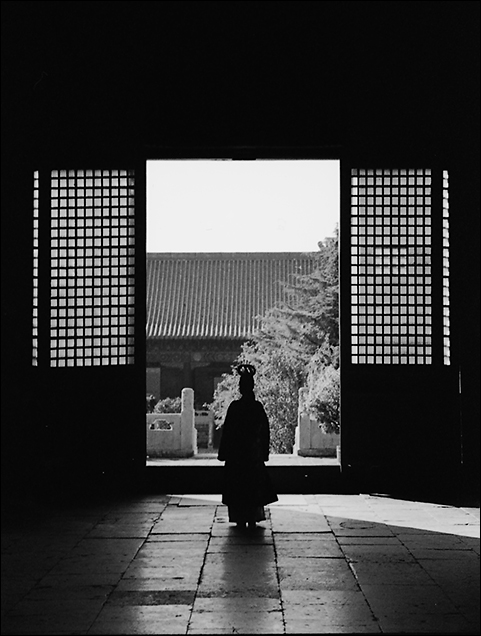

I can’t say I’m that much of a fan of surrealism, being more interested in representational art than this level of abstraction, so forgive me if I gloss over the various other highlights, one of which was a classic vintage Rolls Royce car containing a mermaid – in water! The main draw for me, I’m sorry to say, was more the architecture of the building and the visitors to the exhibits. Here are some images from that session:

All of the images were taken, hand-held, with the Sony A7 camera, in this case fitted with the Zeiss FE f2.8, 35mm lens. The images were processed in Adobe Camera Raw and Photoshop CC, and all but the last image was converted to monochrome using the DxO Optics FilmPack Agfa Scala 200x preset, as a starting point. The final image in the set, above, was converted to monochrome using a black and white adjustment layer in PSCC with modified colour blending and only a single curves adjustment.

All of these images were created using the improved techniques I learned at Ming Thein’s Masterclass in Havana, which I recently attended and more on which in a later post. So, these images incorporate the tonal separation techniques, advanced manual dodging and burning, masked and brushed contrast curve adjustment and soft light blending techniques I worked through to improve my renderings as part of his in-depth workshop. You can read more about that here on my review and here on Ming’s blog report.